Organizational Life Cycle: Definition, Models, and Stages

Throughout their existence, organizations go through various predictable stages, referred to as organizational life cycle. How do organizations experience these life cycles? And how do managerial strategies and actions at critical points in an organization’s development determine organizational design and structure and whether it will succeed or even survive? Let’s find out.

Contents

What is an organizational life cycle?

Why is organizational life cycle essential to understand?

Organizational life cycle models

Small business growth models

Is there consensus?

What is an organizational life cycle?

The organizational life cycle is a theoretical model based on the changes organizations experience as they grow and mature.

Just as living organizations grow and decline in predictable patterns, so do organizations.

Modern sources generally recognize Mason Haire’s 1959 Modern Organizational Theory as the first study using a biological model for organizational growth.

However, the first historical reference we have of organizational life cycles is Alfred Marshall’s 1890 Principles of Economics, in which he compared organizations to trees in the forest.

Marshall described new organizations as seedlings struggling in the shade of their taller neighbors.

The few that survive eventually grow tall enough to dominate their neighbors “and seem as though they would grow on forever,” but ultimately, they decline and fall.

Why is organizational life cycle essential to understand?

You may think the modern era of competitive disruption has made traditional life cycles less relevant, but the opposite is true.

Since most of today’s industry disruptions are in technologies, life cycles and the conditions that shape them are even more critical because of the speed of change. Cycles that once lasted years or decades can now pass in months.

As you will see, if a business fails to take a proactive stance toward organizational life cycle changes, it is likely to fall into crisis and decline.

Organizational life cycles are the product of human behavior. In organizations, that behavior has predictable patterns that result in foreseeable crises. Preparing for those crises can determine whether an organization moves to the next stage of development or fails.

For example, in a stable, mature organization, people fall prey to the misconception that the “way we do things” is the way it will always be. The inevitable result is stagnation.

If leaders and the people understand the issues that can arise before they happen, the change to the next phase need not be a crisis.

Moving on at the right time

An organization can prepare for moving from one stage to another.

For example, when people hold on to policies and procedures to protect their fiefdoms, you have a sure sign that stagnation is taking hold and can take preventative measures by transitioning management before the crisis.

You can also take a proactive stance by seeking to constantly renew, with parts of the company experimenting with new ideas without disrupting the entire organization.

Organizational life cycle models

From the 1960s to the 1990s, scholars and consultants proposed many models of life cycles. Although the models have many similarities, there are differences in the perspectives and the research methods.

We present here some of the most well-known models for comparison.

Lippitt and Schmidt model

In 1967, Gordon L Lippitt and Warren H Schmidt applied personality development theories to the creation, growth, maturity, and decline of a business organization.

Their purpose was to predict the results of handling critical concerns of critical issues in the lifecycle stages of birth, youth, and maturity.

They found that the managerial handling of six predictable crises determined the organization’s developmental stage rather than their size, market share, or sophistication.

Birth

In the birth stage, the critical concerns are creating the new organization and surviving as a viable system. The key issues are deciding what to risk and what to sacrifice.

Youth

In the organization’s youth, those concerns are gaining stability, reputation, and pride.

It is also concerned about how to organize and evaluate itself.

Maturity

In maturity, the organization must concern itself first with achieving uniqueness and adaptability. It must decide how to change itself to sustain its competitive position.

And, it must choose how to contribute to society by selecting what to share.

Here is a summary of the developmental phases according to Lippit and Schmidt:

Developmental stage Critical concern Key issues Consequences if concern is not met Birth 1. To create a new organization What to risk Frustration and inaction 2. To survive as a viable system What to sacrifice Death of organization

Further subsidy by “faith” capitalYouth 3. To gain stability How to organize Reactive, crisis-dominated organization

Opportunistic rather than self-directing attitudes and policies4. To gain reputation and develop pride How to review and evaluate Difficulty in attracting good personnel and clients

Inappropriate, overly aggressive, and distorted image buildingMaturity 5. To achieve uniqueness and adaptability Whether and how to change Unnecessarily defensive or competitive attitudes; diffusion of enerfy

Loss of most creative personnel6. To contribute to society Whether and how to share Possible lack of public respect and appreciation

Bankruptcy or profit loss

Lippitt and Schmidt also give us examples of the consequences of handling or mishandling each of the six managerial crises:

Critical issue Result if the issue is resolved correctly Result if the issue is resolved incorrectly Creation New corporate system comes into

being and begins operating.Idea remains abstract. Company is

undercapitalized and cannot adequately

develop and expose product or service.Survival Organization accepts realities, learns

from experience, becomes viable.Organization fails to adjust to realities of its

environment and either dies or remains

marginal–demanding continuing sacrifice.Stability Organization develops efficiency and

strength, but retains flexibility

to change.Organization overextends itself and returns

to survival stage, or establishes stabilizing

patterns which block future flexibility.Pride and reputation Organization’s reputation reinforces

efforts to improve quality of goods

and service.Organization places more effort on image

creation than on quality product, or it builds

an image which misrepresents its true capability.Uniqueness and adaptability Organization changes to take fuller

advantage of its unique capability and

provides growth opportunities for its

personnel.Organization develops too narrow a specialty

to ensure secure future, fails to discover its

uniqueness and spreads its efforts into

inappropriate areas, or develops a paternalistic

stance which inhibits growth.Contribution Organization gains public respect and

appreciation for itself as an institution

contributing to society.Organization may be accused of “public be

damned” and similar attitudes.

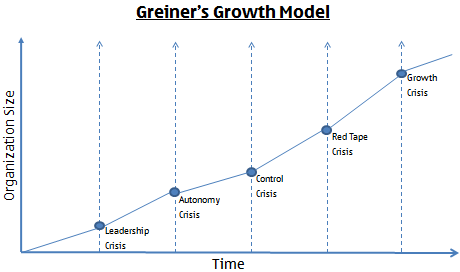

Greiner Growth Model

Larry E. Greiner based his growth model on the age and size of the organization on the premise that organizational practices change over time and that “management problems and principles are rooted in time.”

He based his theory on European psychologists who hold that past events and experiences shape our behavior.

Greiner showed that leaders hold on to obsolete structures to consolidate their power.

So, instead of looking inward to develop the organization, they focus exclusively on external forces. The consequent stagnation leads to revolutionary phases that shake up the organization.

The resolution of the revolution decides whether the company will move forward or decline.

Market forces determine the duration of the evolutionary and revolutionary phases of the organizational life cycle.

When profits are plentiful, evolution prevails, but those profits only buy time before a revolutionary upheaval.

Greiner presents five phases of growth, interspersed by periods of revolution. Each phase results from the previous one and causes the next.

Phase 1: Creativity

In the creativity stage, the organization creates a product and a market.

Leadership is entrepreneurial and visionary, reacting to the market.

The lack of structure and management creates a leadership crisis.

Phase 2: Direction

If the entrepreneurs are savvy enough to engage skilled business management, a structure begins to form, with systems, work standards, and a hierarchical reporting structure.

Phase 3: Delegation

A crisis of autonomy occurs when decision-making is too centralized to be effective.

Organizations try to adapt with delegation, but if the organization isn’t ready, talent will leave.

Successful delegation allows companies to expand but often results in autonomous managers with a parochial attitude, creating a “silo” effect resulting in a crisis of control.

Phase 4: Coordination

A successful reaction to the control crisis is formal systems for planning, control, and resource management.

Eventually, a divide grows between headquarters and field managers, and a “red-tape crisis” results from the organization becoming too large and complex to operate under formal and rigid systems.

Phase 5: Collaboration

If the organization survives the fourth revolution, red tape is supplanted by collaboration, social control, and self-discipline.

Greiner correctly predicted that Phase 5 would create a crisis in the psychological saturation of emotionally and physically exhausted employees breaking under the burden of excessive teamwork and pressure to innovate.

We are already seeing the result of the revolutionary phase as companies now focus on employee wellbeing, rest, and revitalization.

We observe that Phase 6 is already well underway with a different social contract between the organization and its employees, as leaders understand that people are the organization.

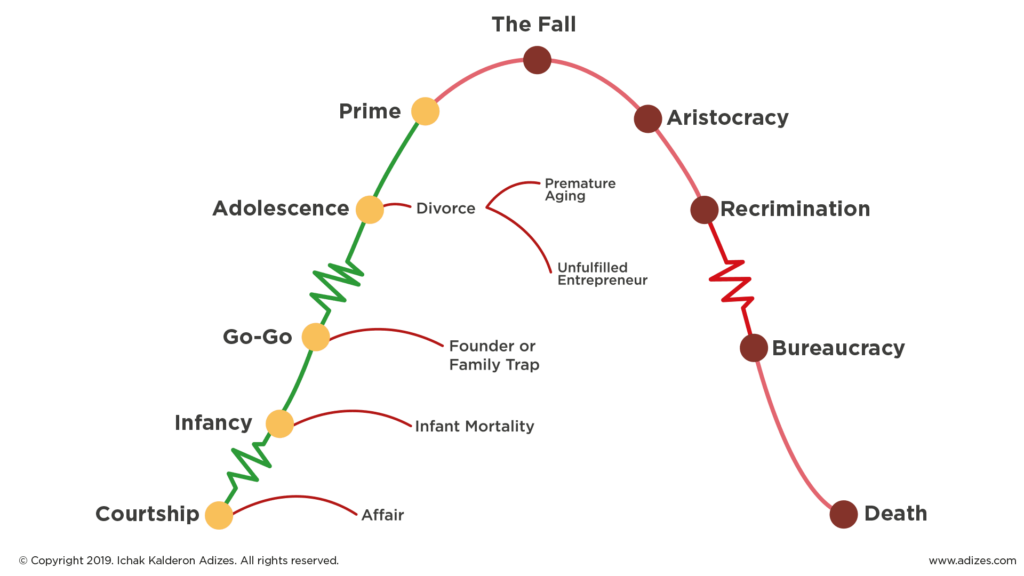

Adizes ten stages model

Dr. Ichak Adizes created his model in 1979 and continues to use it today.

However, his model changes with the times and embraces current technologies and organizational practices.

Adizes theorized that changes in the life cycle occur because of four activities:

- producing results,

- acting entrepreneurially,

- administering formal rules and procedures, and

- integrating individuals into the organization.

Over the life cycle, the organization assumes different roles that determine behavior.

At the foundation of effective management for any organization is the fundamental truth that all organizations, like all living organisms, have a life cycle and undergo very predictable and repetitive patterns of behavior as they grow and develop. Dr. Ichak Adizes

Adizes describes ten stages as the organization grows.

Progression happens when the organization overcomes the growth problems of each successive step.

Courtship

The initial phase is the development of the idea, raising capital, and forming the business.

Infant

As the name suggests, this phase is the start of doing business. The company may experience infant mortality.

Go-go

Things get frantic, perhaps chaotic.

It may experience the Founder/Family Trap, where the business and family life come into competition.

Adolescent

During the adolescent stage, the company begins to define itself and establish its place.

It may experience divorce, either from premature aging or a disappointed entrepreneur.

Prime

During its prime, the organization is fit, healthy, and profitable.

The Fall

The prime phase ends as the business starts to lose its keen edge.

Aristocratic

The organization remains strong because of its successes and presence but loses market share as it falls prey to technology changes and market trends.

Recrimination

Doubt, problems, and internal issues over the decline can cause the company to lose its purpose.

Bureaucracy

Internally focused on process and procedure, the organization seeks an exit or divestment.

It is ripe for takeover at a bargain price.

Death

If the organization can’t renew itself, it closes, sells off, goes bankrupt, or sells its assets.

Miller and Friesen model

Like many other models, Miller and Friesen presented a five-stage predictable pattern.

They based their proposed model on a longitudinal study of 36 large organizations.

According to the reanalysis of their work by Robert Drazin and Robert K. Kazanjian of Emory University, it was a rare opportunity to test empirical data rather than assuming the existence of different phases.

The five phases in the Miller and Friesen study are:

Birth

The firm, less than ten years old, is dominated by the owner-manager.

Growth

Sales are growing by over 15 percent. The company has a functional structure and some formal policies.

Maturity

Sales growth slows, and the company becomes more bureaucratic.

Revival

Sales growth returns, and the company diversifies its product lines.

It has a divisional structure and sophisticated systems.

Decline

Profitability declines as sales levels off and innovation stalls.

Small business growth models

Small business models differ from corporate models in that their success or failure most often rests on the ideas, skills, and determination of one owner, who is the business.

Indeed, reluctance to relinquish control can be the catalyst for failure.

We will examine two examples of models that show how small businesses progress through a series of crises in their quest for stability.

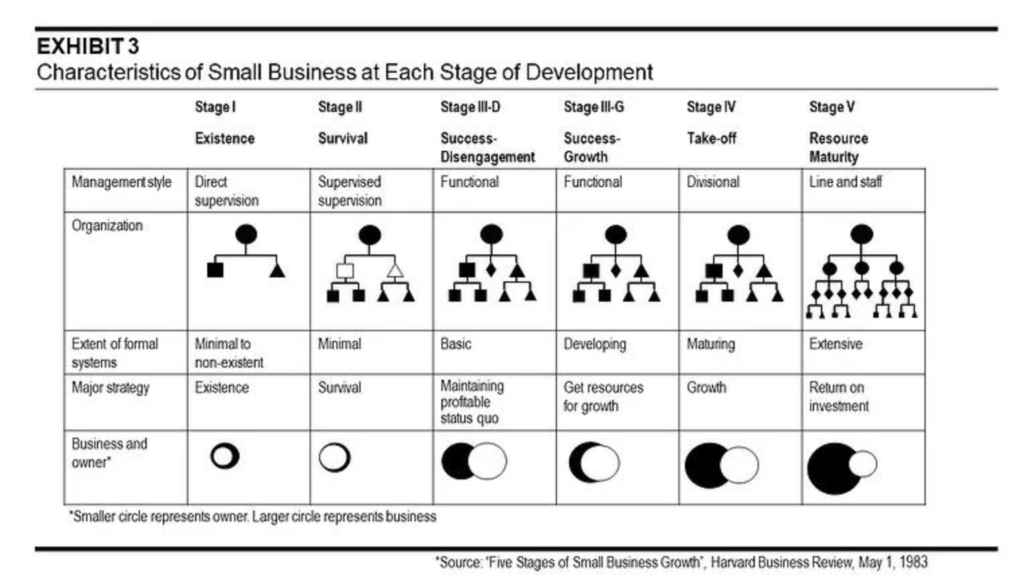

Churchill and Lewis growth model

In 1983, Neil C. Churchill and Virginia L. Lewis examined the life cycles of small businesses. They started with concepts from Greiner and the work of Lawrence L. Steinmetz, who studied the stages of small business growth.

Among other factors, Churchill and Lewis were dissatisfied with previous research that ignored the early stages of growth and inappropriately used only size and maturity as dimensions.

Their model evaluates the size, diversity, complexity, and five management factors: managerial style, structure, systems, strategic goals, and owner’ involvement in the business.

Churchill and Lewis defined five stages of small business growth:

Stage I: Existence

At the existence stage, the owner’s goal is to get enough customers and deliver the product or service to keep the doors open.

The owner does everything, from supervising staff to supplying capital.

The goal is to remain in existence without depleting capital.

Stage II: Survival

If the business survives to become a sustainable entity, it shifts to survival. The goal is to break even and remain viable.

If they can’t move beyond this stage, they sell or close.

Stage III: Success

At this stage, the goal is to achieve economic health—where the owner can choose to remain in this stage and possibly use it as a platform for growth (Substage III-G) or disengage (Stage III-D), hire management, and use it as an income source.

Stage IV: Take-off

In the take-off stage, the primary problem is how to finance and effect rapid growth. Issues are delegation to competent managers and generating cash for growth.

If the take-off doesn’t happen, it reverts to an earlier stage or fails.

Stage V: Resource Maturity

At maturity, the business has the financial resources to thrive, the right people, effective systems, and functional competency.

The goal is to remain viable and avoid future problems.

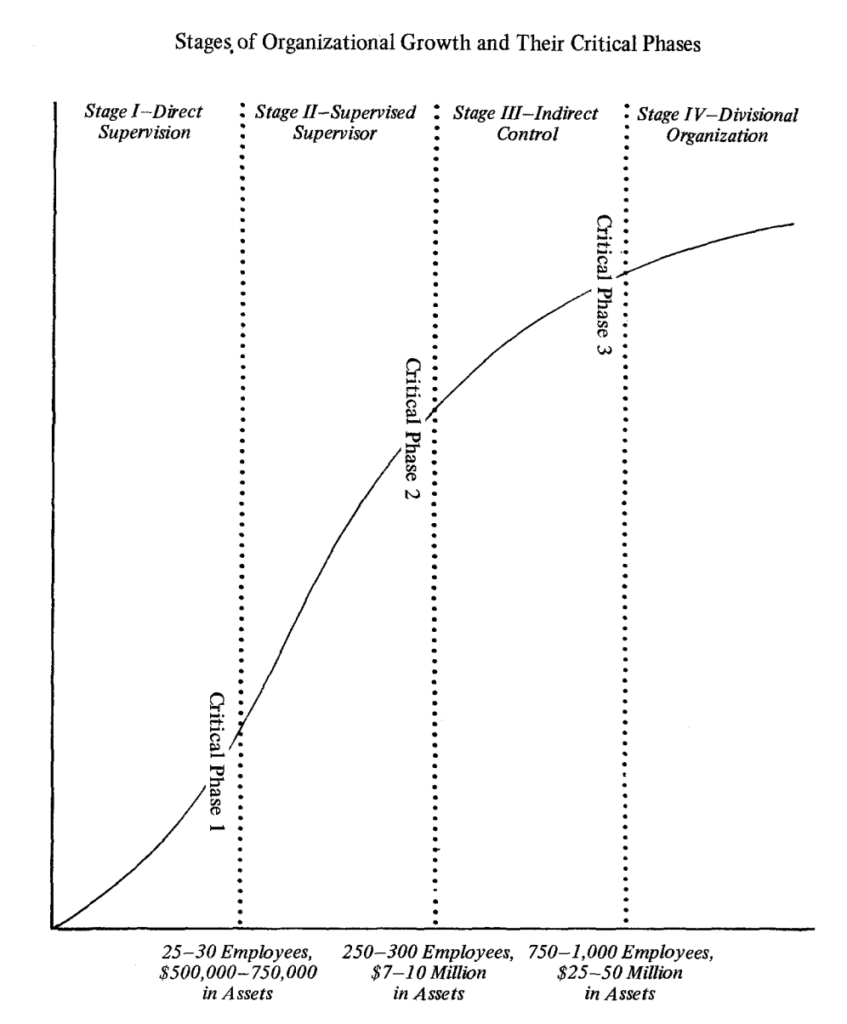

Steinmetz small business growth model

In 1969, Lawrence L. Steinmetz proposed an S-curve growth model for small businesses, with three critical stages.

He described the stages in terms of supervision, from the direct control aspect of a start-up to a divisional, distributed hierarchy.

In each stage, there is a leadership crisis as the nature of supervision changes.

Stage I—Direct Supervision (Live or Die)

In the first stage, the owner’s role as a leader is not based on leadership talents but ownership of the business.

If the business isn’t among the 50% that run out of cash and close their doors (as 50% do), it will increase in size until the owner can’t supervise everyone directly.

Management activities, which the owner may be unqualified to handle, take up most of the day.

If the owner is unable to transition to Stage II, the business will fail.

Stage II—Supervised Supervisor (Being a Manager)

If the business owner adapts to delegation and successful management in the second stage, they can enjoy economies of scale that make it more profitable.

However, a quick rise becomes flatter as the people, production, and organizational issues that afflict all organizations begin to take their bite of profit.

Stage III—Indirect Control (Stability)

Once the business succeeds through Stage II to stabilized performance, the owner must deal with:

- diminishing returns as costs rise to meet income,

- intense, competitive pressures,

- overstaffing at middle management levels and the resultant staff infighting, and

- unprofitable lines of business or ancillary services.

Stage IV—Divisional Organization

If the organization powers through the crisis and achieves Stage IV status, the decisions to be made include remaining a small business, expanding through acquisition or organic growth, or merging with other companies.

Is there consensus?

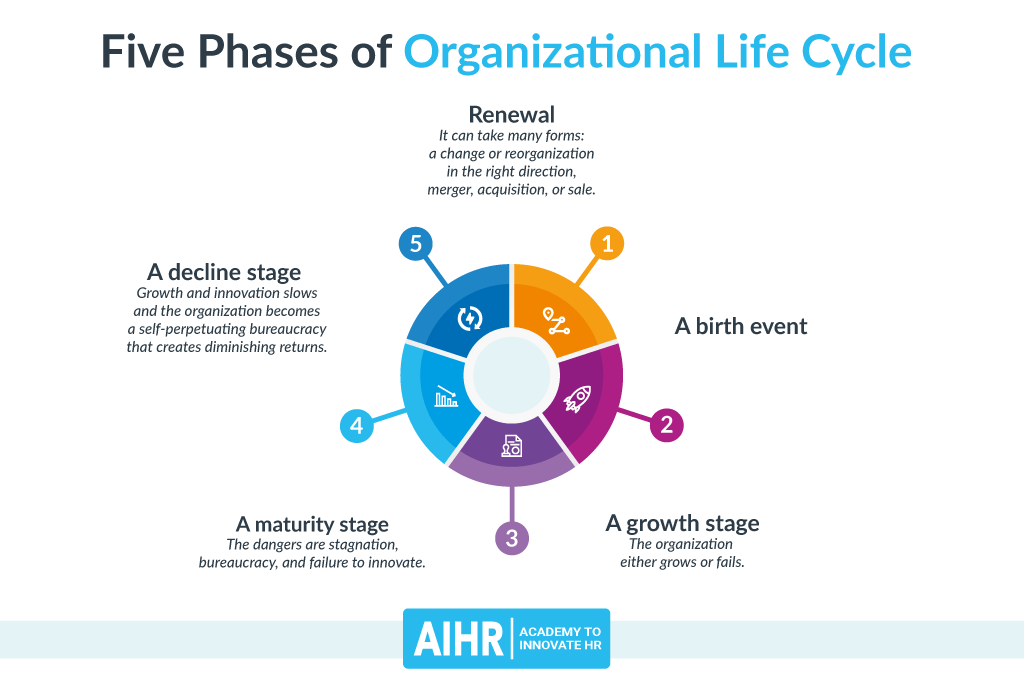

With models that show us three, four, five, or ten stages, it might seem that no consensus exists, but if you dig into the details, you find elements in all of them that parallel the five stages of the lives of living organisms.

- A birth event.

- A growth stage, where the organization either grows or fails.

- A maturity stage, where the dangers are stagnation, bureaucracy, and failure to innovate.

- A decline stage, where growth and innovation slows and the organization becomes a self-perpetuating bureaucracy that creates diminishing returns.

- Renewal, which can take many forms: a change or reorganization in the right direction, merger, acquisition, or sale.

For example, while Lippitt and Schmidt cite three stages, they ignore the decline and renewal. They also posit six critical concerns that demand managerial action, each of which could signal a stage in itself.

The ten stages of the Adizes model are inflection points where intervention is required. Those points have changed to adapt to 21st-century practices.

We now see many decentralized organizations where parts of the business may be in different stages.

They often comprise a stable central core with innovative sub-organizations in start-up or growth phase.

Put your organizational life cycle knowledge to work

If you can understand how an organization evolves in time in each stage of the organization’s life cycle, you can shape your organizational design to achieve your business goals.

The key to success is to begin planning for the next developmental stages early, so instead of a crisis, you have an orderly transition to the next business phase. That way, you’re ready for the new challenges.

And, most importantly, you can prevent the inevitable stagnation that continued success brings.

Weekly update

Stay up-to-date with the latest news, trends, and resources in HR

Learn more

Related articles

Are you ready for the future of HR?

Learn modern and relevant HR skills, online