Employee Well-Being and Productivity: How HR Can Balance the Scales

The fifth industrial revolution is upon us – human and technology collaboration, an increased focus on human well-being, new limits for productivity, and a shift towards renewable resources. As organizations prepare for these changes, a critical question remains on how employee well-being and productivity can coexist sustainably.

Let’s dive into how HR can guide organizations when balancing well-being with organizational productivity in a sustainable way.

Contents

Rethinking our perspective on employee well-being

Defining productivity demands

The relationship between employee well-being and productivity

Defining sustainable employee well-being and productivity

A call to action for HR to move the dial on sustainable employee well-being and productivity

Rethinking our perspective on employee well-being

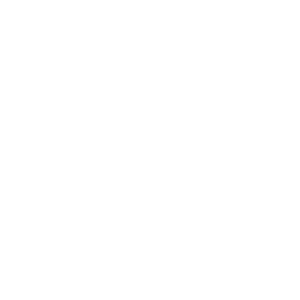

We believe that there are four key shifts we need to make in terms of the current perspectives on employee well-being:

Let’s discuss these shifts in more detail.

Shift 1: Understand that well-being exists on a continuum that is always changing

Well-being should be seen as an ever-present state that changes over time and cannot be static. As such, it is best to think about well-being on a continuum of “Unwell” to “Flourishing.” As human beings, we will shift on this continuum, and it’s important not to look at well-being at one point in time but rather as a trend over a period of time.

Shift 2: Well-being is multi-dimensional

Well-being consists of various dimensions that holistically contribute to the well-being of an individual. None of these are more or less important, and all contribute holistically towards well-being.

| Physical | Healthy habits of nutrition and physical health |

| Mental | Emotional and psychological well-being |

| Intellectual | Meaningful and challenging work that leads toward job satisfaction |

| Spiritual | Congruent alignment between values, self-esteem, and morals |

| Social | Social structures such as family, friends, and community |

| Financial | Ability to meet current and future financial obligations in alignment with desired living standards |

Shift 3: Realize that well-being at work is about the whole human being

Even though work plays a significant role in our well-being, so too do other dimensions such as family, community, and society. For a long period of time, there was a distinction between well-being at work and in personal life, yet as human beings, this is not how we function.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, we saw the need for the whole human being to be considered, especially regarding demands from other dimensions beyond their work-life.

Shift 4: Realize that well-being is a shared responsibility.

A strong misconception is that well-being at work is the organization’s responsibility. This understanding needs to shift.

Well-being is a dual responsibility of both the individual and the organization. Individuals are responsible for their well-being by adopting healthy habits, gaining access to the skills required to be well, and acting in the best interest of their well-being. Organizations are responsible for creating an environment where people can be well and providing access to services enhancing well-being where required.

We discussed employee well-being and mental wellness with Linda Mthenjane, the managing director and founder of The Space Between Us, a human-centered digital mental health platform. You can watch the full interview below:

To understand well-being in the context of productivity, we first need to evaluate the current views on productivity.

Defining productivity demands

Productivity as a concept can be defined as the ratio of output to input. Increasing productivity implies producing more with the same amount of input or producing the same output with less input. We often think about productivity in terms of efficiency or as “doing more with less”.

This definition of productivity worked well in some of the previous industrial eras, where work output was measured mainly by the number of products produced on a manufacturing line. The challenge within the productivity domain is when input and output become more abstract. Consider the example of a knowledge worker responsible for delivering a new marketing strategy. What do input and output look like? In knowledge work, we also find a trend toward measuring outcome instead of output, stating that it is not about effort spent but rather the impact of what the effort delivered.

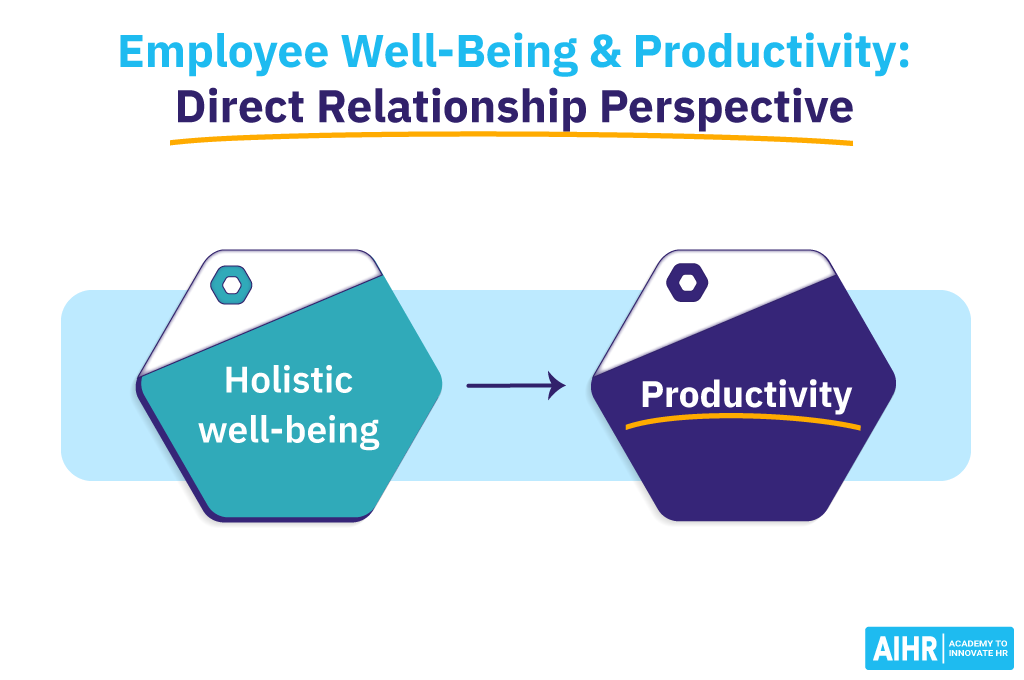

In the changing world of work, we require a broader definition of productivity as how we measure work output has changed significantly. There has been a shift toward better understanding the outcome or impact of work instead of measuring productivity purely based on traditional forms of output. Even though a step in the right direction, this type of thinking largely accepts and proposes that better well-being leads to better productivity. So, in other words, the “more well” the workforce is, the better productivity an organization can expect.

The relationship between productivity and well-being

Most studies, to some extent, view the relationship between well-being and productivity as a direct relationship. This perspective suggests that higher levels of well-being lead to higher levels of productivity.

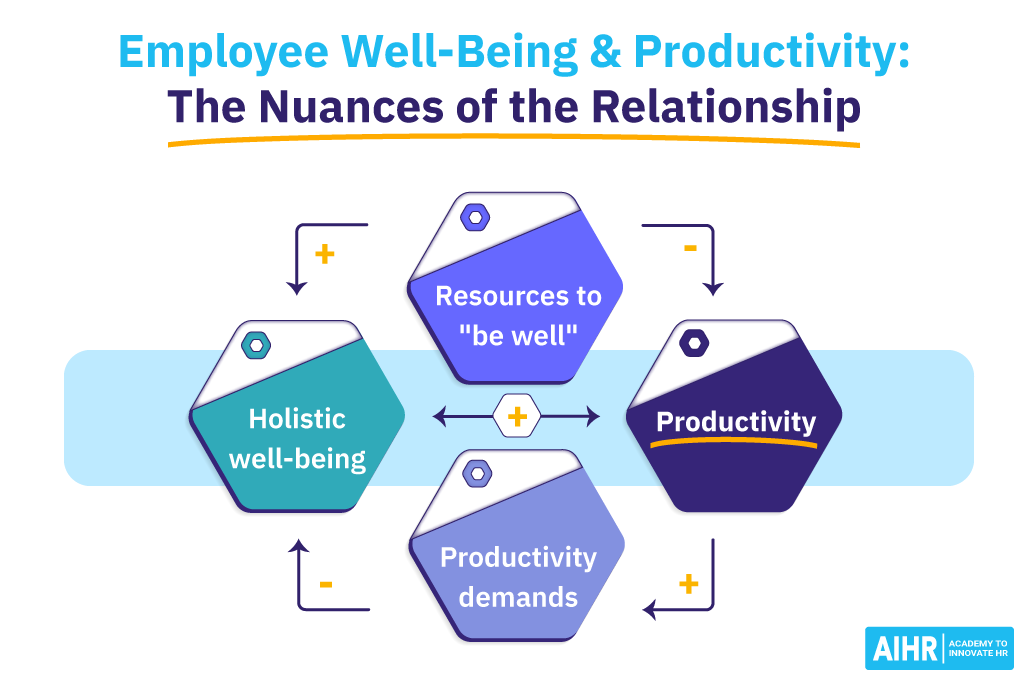

The relationship between well-being and productivity is, however, a lot more nuanced. We also need to consider the balance between job demands and resources as a key contributing factor to this relationship. In this context, demands refer to the “expectations placed upon individuals at work.” Resources “refer to the physical, social or organizational support” available for employees to meet organizational demands.

The balance between demands and resources, part of the theory developed by psychologists Demerouti and Bakker, suggests that when demands and resources are in balance, it leads to well-being and productivity. At the same time, too high demand and a lack of resources could potentially lead to burnout and organizational failure.

We can also argue that more productive individuals can become “more well” as they get satisfaction from the work, which contributes towards well-being, and as such well-being and productivity become a two-way relationship.

By incorporating the demands and resources perspective, the model can be depicted as follow:

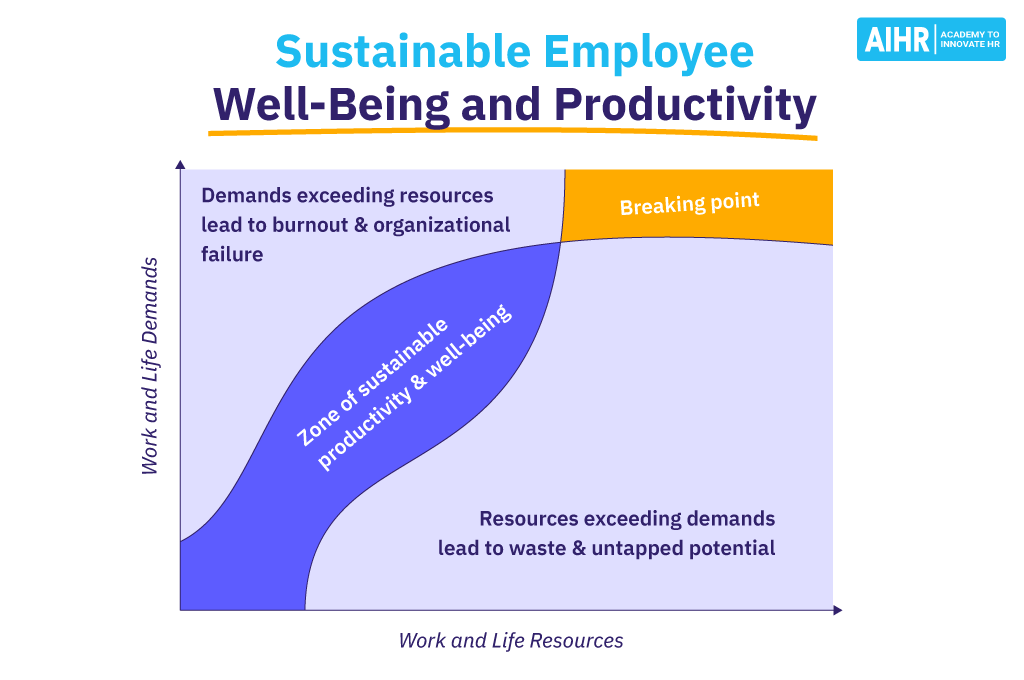

There is, however, another challenge with this perspective. Productivity and well-being do not exist on an infinite curve. At some stage, more resources do not imply increased levels of well-being, nor does higher productivity increase the ability to demand more. We can refer to this as the breaking point – the point where the balancing of demands and resources no longer contributes to the relationship between well-being and productivity.

We also need to acknowledge that context will play a role and that demands could also be placed upon the individual outside work. For example, moving house or dealing with a personal crisis increases the demands on the individual, even though they are not always work-related. The same holds true for resources. At times personal resources can contribute to dealing with high levels of demands at work.

So how can we approach this differently? Is there a way to balance the scales between productivity and holistic well-being?

Defining sustainable employee well-being and productivity

We believe well-being and productivity can exist in a sustainable relationship for both the organization and the individual. To do so, we have to think about productivity and well-being in the context of sustainability.

Let’s start by defining sustainable productivity, which is: “Creating an eco-system that balances the demands and resources required to deliver on the goals and ambitions of the organization in the short and the long term”.

Dissecting this definition, there are a few critical considerations. First, the environment has a balance between demands and resources aligned with the organization’s expectations. In this context, demands refer to work expectations, goals that are being set, and what people are expected to deliver. Resources refer to organizational support, tools, knowledge, and systems, to mention a few.

Second, the organization is still successful, yet it aims for both short and long-term gain and moves away from short-term benefits at the expense of longer-term value. Third, the business can continue to operate in this way for an extended period. By keeping demands and resources in balance, the business can continue the speed and intensity of its operation.

However, this relationship is finite. There will be a threshold where the organization can no longer push higher productivity, regardless of the resources provided. This breaking point can lead to organizational failure, e.g., an overload of systems and production lines. At an individual level, it can lead to burnout, high levels of disengagement, and a loss of well-being.

In this context, we also need to define sustainable well-being. We define sustainable well-being as: “Continuous management of resources for individuals along the continuum of unwell and flourishing by focusing on well-being (mental, physical, financial, social, spiritual) in alignment with work and life demands.”

A reframed approach toward sustainable productivity and well-being

Considering these definitions, sustainable productivity and well-being exist in an interrelated relationship with demands and resources within a particular context of work and life. Keeping demands and resources balanced creates an environment where productivity and well-being can coexist.

As demands rise, so too should the resources individuals have access to, whether at an organizational or personal level, and the “work” and “personal” life should be taken into account.

If resources are more than the demands, this could imply wasted opportunity. Think about the example here where organizations are underutilizing their capacity.

The inverse is also true. Too high demands with insufficient resources will lead to failure. There is, however, a breaking point where increasing resources no longer leads to the ability to deal with demands. At this breaking point, additional support will not result in any additional capacity to respond to demands.

By adopting this approach, the goal for sustainable productivity and well-being is about remaining within the “green zone.” This implies that work and life demands need to be continuously checked against available resources, and available resources continuously evaluated in terms of how they are meeting the set demands. Given the holistic view of work and life, this becomes the dual responsibility of both the organization and the individual.

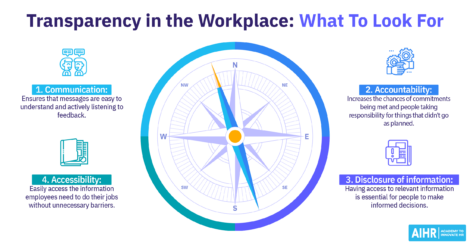

This model is based on transparency in terms of expectations and a much better understanding of what it “takes to get the job done”. It does call for a more data-driven approach toward understanding work and outcomes, how human beings engage with work, and what they want from work. Furthermore, this perspective also requires a greater understanding of the breaking point. Both the organization and the individual have to manage this threshold within the context of work and life.

From a practical perspective, the question remains: How can we shift the current perspectives to balance sustainable productivity and well-being, and what can HR do to drive this change?

A call to action for HR to move the dial on sustainable employee well-being and productivity

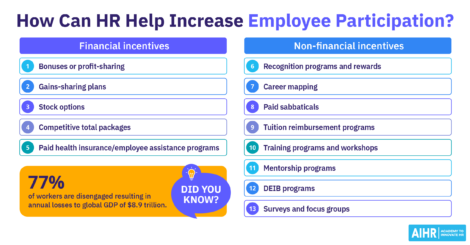

We propose the following actions for HR to guide organizations in this shift.

Action 1: A new approach towards demand planning and goal-setting based upon realistic expectations

HR can help organizations plan in a realistic manner regarding what is expected from employees and how the demands and resources are being balanced.

By using a more data-driven approach, we believe realistic planning and expectation setting can contribute towards more sustainable practices. To do so, we need to break the capitalistic notion of “more is better” and help organizations insert a healthy dose of realism regarding their ambitions, goals, and expectations.

Action 2: Use data and metrics to manage the boundary of the failure threshold.

As HR, we need to help organizations objectively measure well-being and productivity. That allows us to proactively identify the threshold where it is no longer sustainable.

Especially in knowledge work, we need better models of understanding contribution, effort, impact, and well-being as contributing factors. HR can help by adopting a more data-driven approach to designing and measuring work.

Action 3: Educate individuals and organizations on the dimensions of well-being, provide the appropriate access to services and destigmatize well-being

In the shorter term, we need to continue to provide access to the appropriate services for employees to look after their well-being. This does not imply doing away with current employee assistance offerings but rather complementing them via a multi-channel approach that allows for anonymity and participation driven by the employees. Platforms such as OpenUp or Panda provide access to services anytime, anywhere, and on an anonymous basis.

We also need to change the language about what “being well” means and that holistic well-being is a topic that can be discussed openly and dealt with in a respectful and dignified manner.

Action 4: Contribute towards changing the language regarding what a “good worker” is

As HR, we need to break the paradigm that a “good worker” is someone that stays late, is there first, works over weekends, and never says no to any demand from the organization. Instead, a good worker is someone who manages a healthy boundary between demands and resources that aligns with the expectations of the organization and how to deliver within this relationship in a sustainable manner.

Practically, this might call for a re-evaluation of what we celebrate and reward in organizations. We need to take a critical view on whether we are not rewarding behaviors based on effort and not based on impact.

Action 5: Help individuals understand what well-being means for them

At an individual level, well-being means something different for all employees. Our role as HR is to help employees understand the well-being ingredient mix that is suitable for their context, their perspective on life, and their needs. There are great tools available, such as psychometric assessments, that allow employees to gain self-insight into their motivations, needs, and desires and can assist them with planning around their holistic well-being.

In other words, well-being is not standardized. It is a personalized decision of how you choose to approach work and life.

Over to you

As the world of work shifts and evolves, we will require continuous conversations regarding the balance between demands, available resources, and the impact on productivity and well-being. While this debate is not new, we do believe that we require new approaches, new perspectives, and an HR professional that can engage the organization in meaningful conversation about the future of productivity – without sacrificing employee well-being along the way.

Weekly update

Stay up-to-date with the latest news, trends, and resources in HR

Learn more

Related articles

Are you ready for the future of HR?

Learn modern and relevant HR skills, online